All eyes and ears

Words to see or words to hear?

One of the first questions you should ask yourself when crafting a new piece of communication is “Will this be read or heard?”

Answering this question can help you create the best version of your content.

If you’re giving a speech or presentation, your work is to “write for the ear”. If you’re writing a memo or blog post that your coworkers will read, your work is to “write for the eye”.

Knowing the difference can help make sure you’re communicating to your audience as effectively as possible.

Eye, meet left brain

When we’re “writing for the eye” we communicate with readers in a linear way. This type of writing mostly triggers a logical and analytical response - what we colloquially refer to as “left brain”.

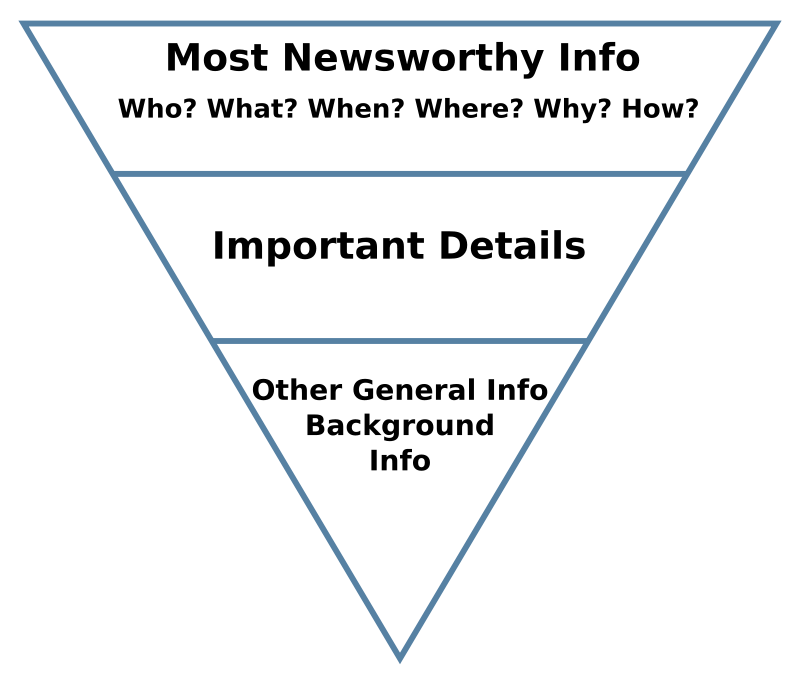

This is the most common type of writing most of us do at work. A great rule of thumb when writing for the eye is to borrow journalism’s famous inverted pyramid.

We start with the lead. Our communication should begin with the most newsworthy piece of information and recap associated key details. After the lead, comes the body of the text. Here we provide the reader with additional information like context, background, precise data, or evidence. Finally, we wrap up with the tail, saving items that are interesting - but not essential - until the end.

In this format, we should keep our words simple, our sentences short, and our tense active.

There’s one important caveat to using this pyramid at work. Unlike a news story, we should follow the tail with a clear conclusion or call to action for our colleagues.

Ear, meet right brain

When we’re “writing for the ear”, we have to quickly grab the attention of listeners with inspirational or personal elements. When speaking, we communicate in a more direct way, often triggering some feeling or emotion - a classic “right-brain” response.

We can disregard the inverted pyramid rule when writing for the ear. Instead of moving from the most important details to least important, the introduction and conclusion become more essential than ever.

We call this "signposting". By highlighting key points in the beginning and the end, you help the listening audience internalise your argument and follow the structure of your talk.

In a spoken format, we can also use speechwriting tricks to put additional emphasis (and focus listener attention) where we want it. Things like anaphora, floating opposites, and triads can all be employed to great effect when you’re writing for the ear.

You can also get away with a bit more when speaking. You can use contractions to make your speech more natural. You can round your numbers or data points, rather than being precise. You can even build to a rhetorical flourish in your closing section.

Wait, what about my slide deck?

In many companies the powerpoint or slide deck has morphed from being a presentation tool (delivered in concert with a speech) into the final communication itself. Slide decks are shared with graphs and bulleted lists of text, while readers are left to figure out how to connect the visual aids with the scant descriptions.

Is this format for the eye or the ear? If you recognise this situation, consider your primary audience. If you’re presenting the topic on a team call (but will share a link after), then you’re really writing for the ear. If you’re hitting send as soon as you finish your slides and your coworkers are left to read it by themselves, you’re writing for the eye.

Next time you make a slide deck that has no complementary spoken presentation, see if you can just write for the eye. Map the contents into a document, blog post, or memo. Forcing yourself to write a narrative this way may even help you get clearer on what you’re saying.

If it’s good enough for Jeff Bezos, maybe there’s something to it (more on that in a later post).